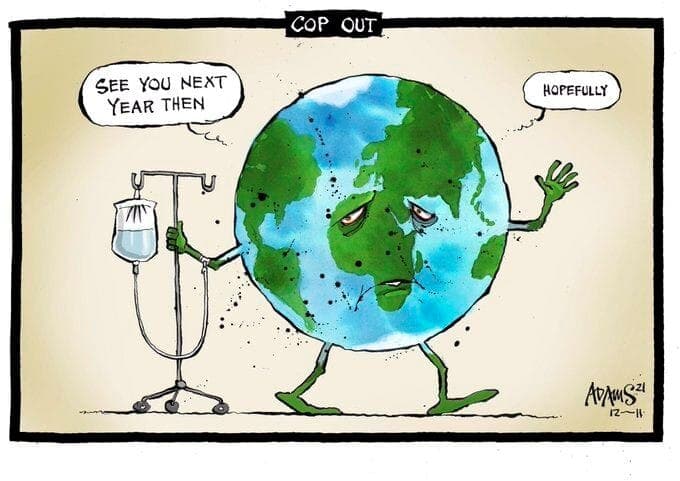

This article, on education and COP26, is the first in a series on schools and climate change education. Subsequent articles will look at national strategies for climate change education, the meaning of eco-literacy, and how leading schools are addressing this issue themselves.

Whatever your view of the process and outcomes of COP26, one thing is certain – the task of leading us across the net-zero line in 2050 will not fall to the politicians who brokered the Glasgow Agreement, but to today’s young people, many of whom are still in school.

But how well is our education system preparing them to become engaged and skilled environmental stewards?

Young people we’ve spoken to recently rated poorly their level of knowledge about climate change on graduating from international schools in Hong Kong and equally poorly their ability to be effective agents of change. What can they really do to make a difference?

A similar picture emerges from more formal surveys around the world. UNESCO’s Learn for Our Planet (May 2021) – a review of how environmental issues are integrated into school curricula in 46 member states – found that over half made no mention of climate change, only 19% referred to biodiversity and more than a third of teacher training programs had no environment-related content.

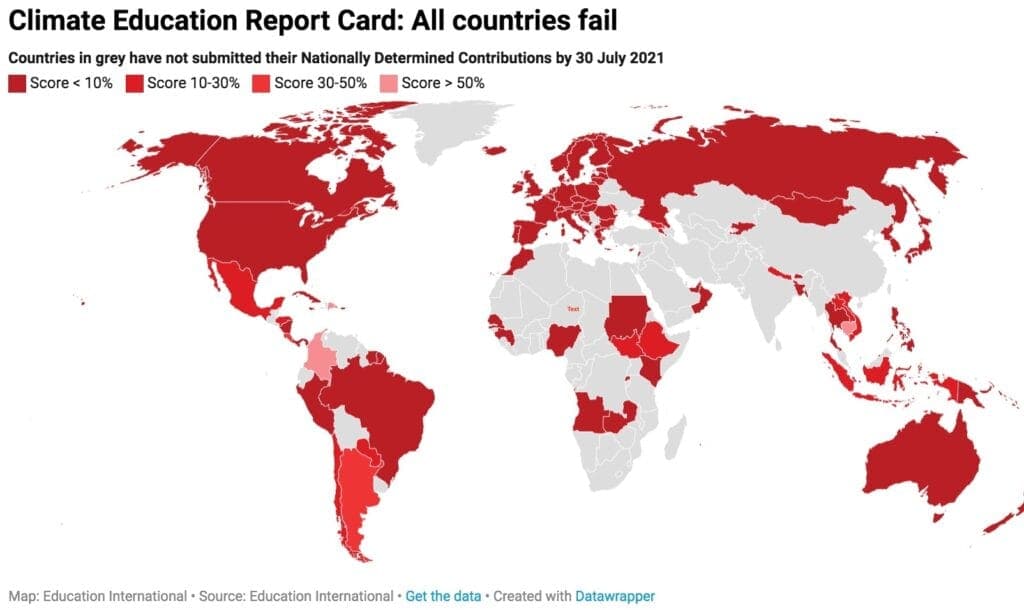

An evaluation by Education International of 73 NDCs prior to Glasgow found that none of them adequately addressed climate education.

Teachers too are ill-prepared. 70% of the more than seven thousand UK teachers surveyed by Teach for the Future in February 2021, felt that they had not been adequately trained to educate students on climate change, its implications, or how to address them.

For the most part, the education sector has been an inaudible voice in the conversation about climate change and, equally, national and international strategies have failed to harness or even recognize the enormous potential for education to accelerate action, relying instead on technology and policy measures. But two recent statements suggest the calls for change are growing louder.

“GCSE’s risk irrelevance” was the Times headline a few days after Glasgow, commenting on the recent HMC working group report on Reform of Assessment which concluded:

“There are significant concerns that our current education system is falling a long way short in offering a relevant education which promotes the breadth of knowledge, skills, attitudes and values necessary for young people to thrive in the modern world”.

In the same week, the Director-General of the International Baccalaureate Organisation, Olli-Pekka Heinonen, writing in Education Review, had this to say:

“Throughout history, schools and teachers have evolved to tackle many of the problems facing human society. As we stand on the precipice of the biggest problem yet, the climate emergency, it’s time for education to pivot again”.

Echoes of these realizations were evident in Glasgow, although they didn’t make the headlines.

Outcomes from COP26 on Climate Education

For the first time at a COP, climate education was an important strand of the agenda in Glasgow. Highlights included:

“…[integrate] sustainability and climate change in formal education including as core curriculum components, in guidelines, teacher training and examination standards and at multiple levels throughout institutions”.

Ministers from Japan, Malawi, Greece, Colombia, Scotland, and UN Economic Commission for Europe were among those to make pledges, along with Sri Lanka, Cameroon, Sierra Leone and South Korea. The predominance of developing countries pledging perhaps reflects the findings by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, that people in developing countries see climate change as more of a pressing problem than those in the developed world.

COP26 also adopted a new work program called Action for Climate Empowerment (ACE) which is essentially a rebranding of efforts to implement Article 12, the article of the Paris Agreement that recognized education and training as necessary to climate change efforts.

COP26 may well have seen the largest youth representation in the history of the climate negotiations. Whereas in the past there has been a tendency towards tokenistic inclusion of young people in the climate discussions, if they were included at all, in Glasgow, the student voice was loud and clear both inside and outside the conference rooms.

Youth4Climate’s manifesto Driving Ambition, formulated at a Pre-COP event in Milan, called on policymakers to open new avenues to young people and empower them to participate in the process of developing and implementing climate action. In response, the final Glasgow Climate Pact included a commitment “to ensure meaningful youth participation and representation in multilateral, national and local decision-making processes.”

Diving Ambition also called on all governments to:

Phoebe Hanson, a spokesperson for Mock COP26, an international collaboration of youth climate activists, presented three simple demands to the Education and Environment Ministers Summit:

Meanwhile, outside the conference halls, the Fridays for Future movement, now in its 167th week of protests (along with other activists’ movements) kept up the pressure on the negotiators. The writer and activist, Bill McKibben, attributes many of Glasgow’s successes (like the phasedown of coal) to the perseverance of these grassroots movements.

Research on social tipping points has identified education as one of six critical levers that can help us to decarbonize by 2050.

Although educational reform is usually thought of as a slow process, the authors highlight examples to show that rapid change is possible: the literacy campaign in Cuba in the 1950s for example, reduced illiteracy from 24% to less than 4% within a year. They also remind us of the potential influence on tipping points a new generation can have once it enters the job market and begins to take its place in public decision making.

Metanoia believes that if we are to equip today’s learners with the skills needed to face the challenge of the climate crisis, we need curricula that champion transdisciplinary learning and student agency. But while we continue to push for system-wide transformations in education, we must also seize the thousands of opportunities to make progress today on every campus and in each school community.

Andrew Brennan, a student who works for a US NGO developing student participation in school governance said it well:

“To the young people passionate about protecting the climate and their communities but don’t know where to start – look to your schools, there is work to be done.”

We need schools to be places where students witness, create, and partake in meaningful changes for sustainability and climate mitigation. We need schools that adopt a whole-school, student-centred approach to sustainability. In the words of Arjen Wals, we need “schools that breathe sustainability”.

Find out more about our student-centered whole-school sustainability audit and how we are helping schools decarbonize at www.metanoia-eco.com.